ARTISTS in MUSEUMS

About

The ARTISTS in MUSEUMS project partnered Alice Springs based artists with local museums and heritage buildings to create a suite of site-specific pop-up exhibitions displayed from 11 May – 16 June.

Artists can bring fresh eyes to a museum collection, tackle concepts that are hard to explore, spark new conversations, challenge established ideas and offer new insights. Projects of this nature encourage interrogation of collections to highlight their contemporary significance alongside their historical value. They engage audiences in new ways ensuring that collection and heritage buildings are used and enjoyed to their full potential.

The site-specific nature of this project afforded the opportunity for artists to stretch their studio practice in new directions and to reflect on the layered histories where they live.

30 artists created work in response to 6 venues. You can download the ARTISTS in MUSEUMS trail here.

ARTISTS in MUSEUMS is a joint initiative between Artback NT and the Women’s Museum of Australia.

Megafauna Central

|

Tara Leckey has a Batchelor of Arts (Hons.) in Interior Design from RMIT, Melbourne. She has worked in arts administration for 25 years throughout regional and remote areas of Northern Territory, Queensland and Western Australia. Recent years has seen Leckey study and experiment with ceramics and mixed media. She has participated in a number of local and national exhibitions. Remains For a long time, I have collected material fragments from abandoned settlements in remote areas. This may be controversial. We are not supposed to pick up the debris left by our forebears, but I am compelled to scan the ground and look for treasures. This fascination with broken pottery, buttons, buckles, pieces of tin and glass, stems from my interest in frontier history. My history. I have spent time in the small town of Beltana at the edge of the Flinders Ranges, where early fleets of camels were stationed prior to their arduous journeys into the interior. ‘Remains’ points to the things that can still be found in the area, 150 or more years since it was ‘settled’. The nearby copper mine at Sliding Rock stands silent. A ruin surrounded by glinting coloured glass and a blanket of tiny pottery shards. I think of the camels and their loads, still evident in the creek beds and wind swept hills. |

|

Tangentyere Artists is an Aboriginal owned and run, not-for-profit Art Centre in Alice Springs, supporting emerging and established Town Camp Artists through the gallery, studio and outreach programs. The Art Centre supports Indigenous Artists visiting Alice Springs from remote communities, offering a safe place where people can sit down to paint. Mega Mob This was the first time we went to the Megafauna Museum. We didn’t know about it before. It used to be a bank. We saw that giant bird, the old kangaroos, animal jaws and all the other bones they found covered in sand. These reminded us of the bible days, the time of Christianity and of family stories from the old times. Maybe there were giants long, long before us, so we painted them. We might go back to Megafauna one day, awa! |

|

Yarrenyty Arltere Aritsts is a not-for-profit, Indigenous owned and managed arts enterprise. It is part of the Yarrenyty Arltere Learning Centre, an inter-generational program that began in 2000 as a response to the chronic social distress faced by families. It is a small dynamic art centre situated in the Yarrenyty Arltere Town Camp adjacent to the Desert Park in Alice Springs. The Art Centre is a place people come to work, destress, share stories, plan for the future and create extraordinary and innovative art. The enterprise provides both social and economic outcomes, for the artists, and their families. Mega We saw bones and crocodiles. Big things and dead things. We saw trays of insects in rooms behind the museum. We thought if that crocodile lived here in the desert now we wouldn’t go swimming. We thought if that big bird lived here we would want to go hunting! We are Yarrenyty Arltere Artists and we are the sewing people. We make soft sculptures from blankets we have dyed up with local plants. We pick the wool colours like a painter picks paint. We think up what to sew in our head from old stories and new stories from looking all around us and getting ideas. We thought of creatures for this exhibition that might have been here a long time ago. Maybe they are real and maybe not. It doesn’t matter because when we sew we feel like they come alive in our hands. They are real to us. |

The Residency (until 9 June)

|

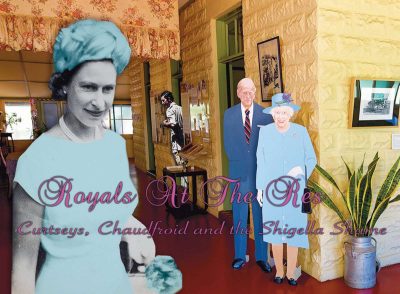

Pip McManus is an Alice Springs based visual artist, working across an array of media including video, ceramics, bronze and steel. Her art practice encompasses studio work, exhibition participation and public art commissions. McManus is a founding member of Watch This Space Artist Run Initiative. HRH at The Residency When researching to create a display on Royal Visits to Central Australia, with particular reference to the 1963 tour, I thought accessing official records would be straight forward. Alas, copyright fees and conditions are costly and restrictive. However, the hidden silver lining of theses encumbrances uncovered a wealth of local home movies, photos and first-hand accounts detailing early visits by the royal family. Republicans and royalists alike chuckle in recalling childhood memories of the young Queen, sailing past in a big black car, white gloved hand tilting at the waiting crowds. Anyone unfortunate enough to attend a special event at the Residency for Prince Charles’s Jubilee visit in 1977, including the Prince, has indelible memories of a shigella infection which shortly afterwards afflicted all the guests who had enjoyed the sumptuous buffet luncheon. |

|

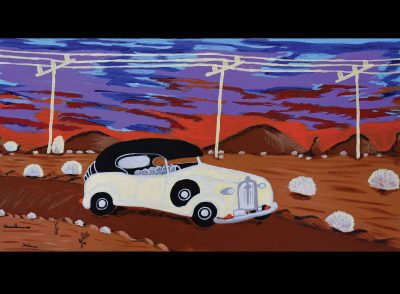

Maureen O’Keefe is an artist and writer residing in Alice Springs. Her family come from Karlu (Devils Marbles) where the Kaytetye and Walpiri people lived before they were moved to Warrabri (Ali Curung) where Maureen was born in 1969. As a young person O’Keefe learnt wood carving from the women in her family. Later in life she worked as an interpreter and translator for documentary films. She is dedicated to recording her family stories in image and text. Car Portraits When I saw the photos of camels and cars in the old house where the governor used to live it got me thinking about all the different ways my family have travelled around and all the stories they have told me over the years. The missionary lady Ms Annie came through Barrow Creek from Adelaide in a horse and buggy. She picked up my father’s mother, Nita, and her sister, Molly and took them to Tennant Creek Telegraph Station – 7 Mile they called it. That’s where they were raised up in the dormitory there. This is my history. That horse and buggy is part of that story. This is a story that needs to be told. It’s a lost history if I don’t tell it. It’s important to tell these stories so they are not forgotten. It’s a story about survival. |

|

J9 Stanton studied Fine Art, majoring in sculpture at the Victorian College of the Arts and worked on various public art projects at Down Street Studios in Collingwood prior to moving to the Northern Territory 17 years ago. Stanton’s practice encompasses public art and welded sculpture and the exploration of 3D drawing. She works closely with Yarrentye Arltere artists to assist them with the production of soft sculpture. Lace Tools The tsunami of advances in 3D printing technology foreshadows an impending amnesia for a plethora of skills known and practiced for centuries. Production of intricate design work in metals, wood, plastics or just about any materials we can imagine, are, and will be taken over by mechanized processes and cyborgs. The boundaries for the very act of making art have once again taken a quantum leap. The relevance of the handmade takes on a completely new significance, or insignificance. This artwork has been HAND drawn with a 3D pen, producing extruded plastic lace. It reflects on the cross roads of computer-aided technology, juxtaposing the masculine art of blacksmiths and the feminine craft of lace making, connecting old and new methodologies for creating. |

|

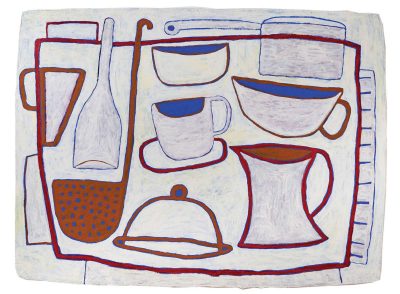

Marina Strocchi moved to Haasts Bluff in 1992 to establish the Ikuntji Art Centre. Strocchi has exhibited throughout Australia, USA and Europe with work represented in public and private collections nationally and internationally. In 2015, a survey exhibition with accompanying catalogue toured the Northern Territory. Strocchi has three solo exhibitions this year, ‘Coastal at Artitja’ in Freemantle and ‘Terra Firma’ at Jan Murphy Gallery, Brisbane and ‘Terra Firma II’ at Australian Galleries, Melbourne, resulting from a residency at Kangaroo Valley in 2018. Still Life My work is an intuitive response to nature, in particular the Central Australian desert. Through layering of textured mark making I create the subtle irregularities and patterns of a world where nature is the major stakeholder. The tension between the interdependent line work and form creates the counterpoint for the structure and colour in my paintings. I attempt to create spacial harmony, a place of reprieve and refuge, as nature does in life. My painting practice uses acrylic paint and oxides on linen or hand-made recycled Indian rag paper. This body of work references the objects that clutter our worlds, old and new. The works pay homage to the familiar objects that get us through a barbeque or a coffee. Teetering between representation and abstraction they evoke a world that was slower paced and less complicated, a world that is captured within the confines of The Residency. |

Adelaide House (until 24 May)

|

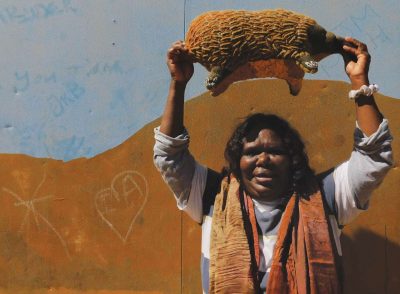

Tjanpi Desert Weavers is a social enterprise of the Ngaanyatjarra Pitjantjatjara Yakunytjatjara Women’s Council that enables women living in the remote Central and Western deserts to earn an income from fibre art. Tjanpi has a public gallery in Alice Springs, exhibits work in national galleries, facilitates commissions for public institutions, and holds weaving workshops. Representing over 400 Aboriginal female artists from 26 remote communities who make spectacular contemporary fibre art in the form of baskets and sculptures. Tjanpi field officers visit these communities to purchase artworks, supply art materials, hold skills development workshops, and facilitate grass collecting trips. Minyma Tjirilyanya Ngaltutjara Pikatjara (Echidna Woman Hurt and Sick) Created at the site of the Two Sisters Tjukurpa on the APY Lands near Pukatja (Ernabella) in South Australia, this collaborative artwork tells the ancient story of Minyma Tjirilyanya (Echidna Woman). It is a story about rescue and care, but also about inevitable death. The artists convey themes of coping, caring for the sick, being rescued against all odds, and surviving. They see a reflection of their own lives. In daily community life, women are often out seeking what is needed to sustain their families, and through this artwork they express that resilience and strength. |

Old Hartley Street School

|

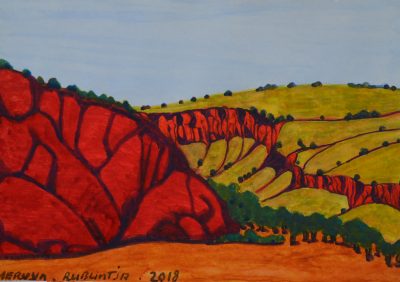

Hermannsburg Potters In 1990, senior Ntaria law man, Nashasson Ungwanaka, invited accomplished potter and teacher, Naomi Sharp, to come and teach pottery to families, many of whom at this time were living on their traditional Country at outstations. With access to her expertise and the use of one kiln, the potters began to produce the startling and exciting pots for which they have become renowned. Now master ceramicists in their own right, the Hermannsburg Potters have an extensive career exhibiting widely throughout Australia and internationally. Their work is held in major public and private collections nationally and internationally. |

|

Iltja Ntjarra – Many Hands Art Centre is the home of the Namatjira watercolour artists. The Art Centre is a not-for-profit organisation and is Aboriginal owned and directed. Operating since 2004 to provide a place for Western Aranda artists to come together to paint, share and learn new techniques and ideas. The Art Centre is strongly committed to improving economic participation of Aboriginal people and maintaining cultural heritage. Iltja Ntjarra has a special focus on supporting the Hermannsburg School watercolour artists, who continue to paint in the tradition of Albert Namatjira, arguably one of Australia’s most famous artists of the 20th Century. Albert Namatjira taught his children to follow in his unique style, who have since passed this knowledge onto their children, which has resonated in a legacy of watercolour artists in the Central Desert region. By continuing his legacy, these artists continue an important piece of living history. Wurmarla Kaltjirritjika – listen and learn When I was a kid my family brought me to this old schoolhouse to show me around. There used to be Aranda kids in this classroom together with the non-Aranda kids. The Bungalow kids came here to this school. Back in those days they divided the Aboriginal kids from their families. Charlie Perkins and his brothers came to school here. We wanted to bring some Aranda stories and language into this old classroom. We learn from family about language and culture. We pass it on through paintings and stories. We are proud of our Hermannsburg School. Nowadays you see mining everywhere destroying our Country. These paintings keep the memory of Country and culture strong for future generations. |

Women’s Museum of Australia

|

Suzi Lyon is an accomplished artist, arts educator, mentor and champion of the arts sector in Central Australia. As a multi-disciplinary artist, her practice encompasses ceramics, printmaking, drawing, photography, textiles, animation, immersive digital, sound and live art. She is a senior lecturer in Visual Arts at Charles Darwin University, exhibits regularly in the Northern Territory and nationally and has undertaken residencies in China and the Arctic. Lyon’s work is deeply grounded in her concern for the environment and how it is impacted. Disambiguation As much as museums are keepers of memories through preservation of tangible objects and paraphernalia, they also speak of absence. Within a built environment, we move in and amongst layers of both present and past, what is known and what is not. Still, layers exist, as memories that we can acknowledge, or as a resonance that may always pervade. The grounds and structures of the Alice Springs early jail, hold particular memories and stories. This drawing eludes to what was once present on a now well-kept grassy area – one of a number of cage like structures that housed inmates, long since demolished. The process of rendering hard metal bars onto a large scale, soft and flexible material was curious. When gathering it up holding it as a mass, I felt it to be something tender and sad. I see museums as places where we may carefully not forget. Perhaps they are everywhere. |

|

Mel Robson is a ceramic artist based in Alice Springs who creates functional objects, sculptural works, installation pieces and public art. Her exhibition practice centres around ideas of place and identity and the ways in which histories, stories and associations can become embedded in everyday objects. Exploring this relationship between objects and personal narrative, Robson creates evocative and contemporary works that weave together the past and present. Mind the Gaps Using both found objects and imagery from the collection of the Women’s Museum of Australia, this site-specific installation celebrates and questions the telling of histories and stories in Central Australia. Found ceramic objects and imagery have been transferred onto ceramic tiles and embedded in the cracks and gaps of the museum walls and footpaths creating brief glimpses of past and fleeting traces of history. This work draws attention to the complexities of interpreting history, the way stories get remembered or forgotten within dominant narrative, and the role objects can play not only in how we remember but also in how we forget. |

|

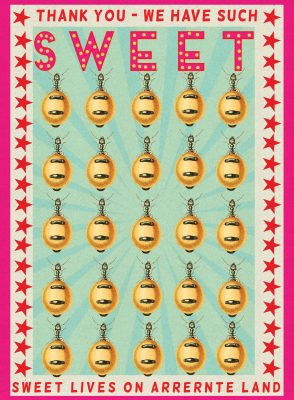

Nicole Sarfati has a Batchelor of Fine Arts and Communications, her work reflects this mix, utilising the visual languages of commercial design with the stories of fine art. Sarfati does not see herself as an artist but rather as a curator arranging colours, words and images, incorporating the use of collage and public domain images. Migration Having an ethnic background was mostly embarrassing growing up in the seventies in suburban Australia. It was still quite stigmatised and I tried to hide any reference to being a ‘wog’. Having an immigrant father and a blond blue-eyed Aussie mother meant I went to both church and the synagogue. I grew up listening to conversations that used three languages in one sentence, depending on what language best transferred the meaning. Now, I love this mix of culture in clothes, decor, food and perception. It is a great honour to work amongst the stories of the women in the exhibition ‘New Voices New Relationships’. I can only imagine the courage and strength needed on their journeys to be here. To these women I say, thank you for adding colour, culture, depth, beauty and FOOD! to our lives here. I would like to acknowledge most of us are new visitors to this ancient Arrernte land. Thank you we have had such sweet lives on your Country. |

Museum of Central Australia

|

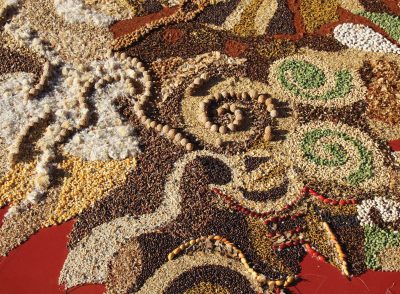

Franca Barraclough is a multidisciplinary artist who works across photography, installation, performance art, live arts, theatre, dance, design and illustration. She is an artist of diversity whose practice is fed by the cultural and environmental nuances of Alice Springs. Barraclough is a designer of the collective imagination of place, the hot, complex, maverick filled wonderland of Central Australia. Her work retains an unpredictable characteristic of unfettered oddness, as she draws upon local detail and international mythology. Seeds and Civilisation Civilisations are merging. The seeds from the lands of our shared heritage are being blown by the wind along the roads travelled as new homelands are found. Cultures are not static, constantly adapting to new environments and circumstances, merging like seeds and plants to form new environments and new cultures. Seeds and grains are the little parcels of embryonic food potential that have allowed civilisations to move across vast distances and thrive in remote and harsh terrain like Central Australia. Humans have played a big role in transporting and dispersing seeds from their geographic origins. Patterns of seed dispersal reflect the intersection of cultures and their relationship to the natural world. |

|

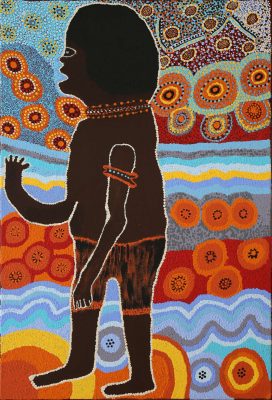

Bindi Mwerre Anthurre Artists have been operating within Bindi Enterprises in Mparntwe (Alice Springs) since 2000. The Bindi Mwerre Anthurre Artists studio is the first in Australia to occupy the intersection between supported studios and Aboriginal Art Centres. Artists are represented from communities across the Central Desert region, Kaltukatjara (Docker River) to Yuendumu. Exhibiting nationally, Bindi Mwerre Anthurre art is highly sought after by galleries and private collectors for the distinctive way it captures the beauty, humour and essence of Central Australia. Adrian Jangala Robertson was born at Papunya in 1962. His Fathers’ Country travels from west of Walungurru through Karku, Nyirripi to Warlukurlangu, Yuendumu. Robertson’s late Mother, highly regarded painter, Eunice Napangardi, is the Country, Yalpirakinu, that he paints. Beautiful Art Made Proper Way hangs amongst the museum displays of ecosystems, geology and palaeontology that describe the region and its history. The works forge together strong knowledge and connection to this land, offering a complimentary perspective of both its physical and social landscape. |

|

Neridah Stockley trained at the National Art School in Darlinghurst majoring in painting and has lived and worked in Central Australia for 18 years. Stockley’s artistic practice includes drawing, printmaking, ceramics and collage. Her work is held in various public collections including Artbank, Parliament House Canberra, Newcastle Art Gallery, Macquarie Group and Charles Darwin University. Stockley regularly exhibits in the Northern Territory and across Australia, most recently in the Guirguis New Art Prize at the Art Gallery of Ballarat. She is also a recipient of the Arts NT Creative in Residence for 2019. From Hermannsburg to Horseshoe Bend Stockley’s work is about relationship to place. Urban, remote, coastal and domestic landscapes are long standing motifs. Looking for the aesthetic value in daily prosaic things, her approach to landscape is often domestic in scale. Stockley’s practice has recently seen the introduction of ceramics as a new medium for expression. ‘Raw material’ is a term she often thinks about, how to handle and resolve paint, paper and clay. In this, she has deliberately made simple forms to act as a support for mark making, much like paper or board, interested in the visual tension between 2D and 3D. The paintings and ceramic vessels on display are about the Lutheran mission at Hermannsburg and Horseshoe Bend, markers of domestic and industrial structures in form and imagery. Stockley is interested in the macro elements of shelter, the awnings, tin, brick, shadows, doors, windows, water tanks; the canopy of Carl Strehlow’s buggy; hills and desert landscapes. |